My grandfather was ethnically Jewish. We called him by the French Grandpapa, as he lived in Montreal for most of his life, but his name was Ladislav, later anglicised to Les or Leslie after he immigrated to Canada. He passed away in 2018, and afterwards, I felt quite uneasy about his death. This was not only because he was my grandfather, but also because Grandpapa had not been a happy man in life.

It can be hard to accept unhappy endings. When a loved one passes, it can often be comforting for those left behind to know that the departed had lived a joyful and fulfilling life. But though Grandpapa had had moments of contentment, and our family did our best to support him, he never seemed like he could find actual, lasting happiness. After fleeing war-torn Europe in the 1940s, the Holocaust left a stain on his life that could not be removed.

Despite Grandpapa’s pessimistic nature, he was a talented man. In his prime, he was an engineer, but he was skilled with both numbers and the arts. He had a love for jazz and had an impressive CD collection, and he spoke five languages, including Czech, German, and Russian. He was also quite a skilled photographer, and impressively proficient with technology despite his age–I recall him teaching himself how to use PhotoShop while my other grandparents were still refusing to get email.

Despite his talent and potential, however, Grandpapa suffered from undiagnosed depression and PTSD. This exacerbated his pessimism, and negatively affected many of his interpersonal relationships. His personality very much resembled the character of Vladek, another Holocaust survivor from Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus. Maus is based on the true story of a Jewish refugee from Poland, told from the perspective of Vladek’s son, Art. Through his storytelling, Art represented how the Holocaust had deeply affected Vladek’s psychology, and damaged his intimate relationships. While Vladek loved his son for example, and would often complain that Art didn’t visit him enough, whenever Art did actually visit, Vladek was inclined to casually disparage him, in a way that would inevitably push Art further away.

This behaviour can be common with trauma survivors. British psychiatrist John Bowlby theorised that this style of relating to others can arise when a person develops a “disorganised” or “fearful-avoidant” attachment style. He theorised that this developed in children with traumatic childhoods, as they were not able to know what to expect from their caregivers. This affected their ability to connect with other objects of attachment even into adulthood. While the grown child would unconsciously desire love and affection like anyone else, they may attempt to obtain it in ways that seem illogical or paradoxical. Someone might for example behave like Vladek–craving love, and asking why he can’t receive it, while simultaneously insulting and criticising the person that was trying to provide it.

Grandpapa was born in 1929, in what was then-Czechoslovakia. The details of his life story could sometimes be confusing based on his personal accounts. I’m told this is not uncommon in oral storytelling and cases of trauma—Hitler and the Nazis annexed the Sudetenland in 1938, occupying the country until 1945. As Grandpapa had learned that his Jewish ancestry was dangerous, he did not even reveal to his sons for a long time that they were even Jewish until they found out about it on their own. Even afterwards, some of his stories remained occasionally vague or contradictory.

We do know some details, however. We know Grandpapa’s father Hugo died when Grandpapa was quite young, beaten to death by anti-Semitic Austrian police prior to the Nazi occupation. His mother, Margarete, survived the Holocaust, but spent some time in the concentration camp Terezin before fleeing the country. She remarried Hugo’s brother, Arthur. When Margarete and Arthur fled Europe in the 40s, they left Grandpapa behind by himself.

Again my details are fuzzy here. Because Grandpapa only ever provided details that were fuelled by anger and hurt, I am not entirely sure why he was left alone in Czechoslovakia. We do know, however, that his family did send for him eventually. I’m not sure if it was their plan the whole time, however, as this information was not gleaned from Grandpapa directly. My father learned how Grandpapa escaped when his brother came across a website link and my dad came across an invitation that gave us more clues about Grandpapa’s past. My grandfather had been invited to a reunion for Jewish refugees who had escaped Czechoslovakia in the same way.

We learned that my grandfather had been transported out of Czechoslovakia as a child by a man named Nicholas Winton. Winton was known as “Britain’s Schindler.” He coordinated Britain’s Kindertransport operation, which allowed for unaccompanied Jewish children to escape the Czech Sudetenland. They were granted temporary asylum in the UK. Winton saved 669 children, one of which was my grandfather—his name can be found on the list of children saved.

Grandpapa thus survived the Holocaust, eventually making his way to Quebec. But unfortunately, like with many other survivors, the effects of that trauma stayed with him forever. He never told us everything that happened in Europe during the time he had been there alone, but he had little good to say about the world afterwards, and always had a very difficult time trusting people, or ever accepting support.

You may wonder about the title of this article, and why I am writing my grandfather’s story now. It’s because after Grandpapa’s death, I thought a lot about trauma and what it did to him, and also about how challenging and complicated it was to try and provide support after so much harm had been done. I wondered if there was anything that we could have possibly done while he was alive to help him feel happier. I even took an internship working with refugee survivors of torture to try and understand what might help people with PTSD most. But while those with trauma always deserve to be supported, and though there were some things my family and I were able to do to improve things while my grandpa was alive, ultimately, that trauma could never actually be “cured.”

When I think about honouring Grandpapa’s memory, and the memory of other Jews murdered during the Holocaust, I feel very sad to consider in our current geopolitical climate. It is tragic that the trauma of the Holocaust was weaponized and fuelled into additional hate and violence against innocent Palestinians. The term “anti-Semitic” now has been weaponized to shield Zionists against any criticism, a disservice not only to the Palestinian people, but to Jewish victims of the Holocaust. They suffered and died only for future generations of the world to not take any of those lessons to heart.

As someone who is descended from the Jewish diaspora, I am familiar with what true anti-Semitism is, and its possible effects. Anti-Semitism led to my Great-Grandfather Hugo being murdered. It led to my Great-Grandmother’s time in Terezin, which created trauma that led her to eventually taking her own life. It led to a fearful, awful childhood for Grandpapa, who had to flee his home country, in danger and alone. But it is not young students asking their universities to divest from war crimes, and it is not to be used as a shield to protect a country and government responsible for a genocide.

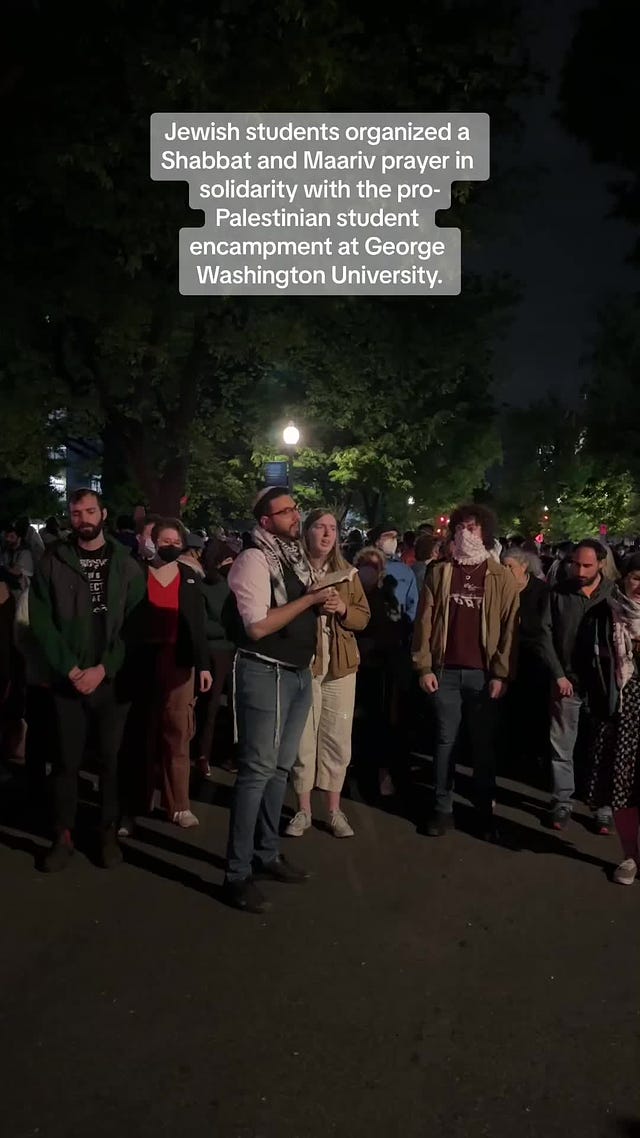

Most Jewish people understand this well. There are many people with Jewish ancestry across the world who recognize that “never again” means “never again” for everyone—all ethnic groups, all people, everywhere, now and into the future. I saw a very beautiful clip the other day of Jewish students who organized a Shabbat and Maariv prayer in support of the pro-Palestinian protests at George Washington University. It was a beautiful reminder that trauma does not always have to beget more trauma.

I have always wondered what might be the best way to honour the memory of my grandfather. For me, supporting a Free Palestine has become an important part of it. Thousands of people have had to suffer since World War II because of ethnic hate. At some point, it must stop. The world must learn its lesson. What happened to my Grandpapa was a trauma that lasted for his whole life. But he is only one story amongst many stories—to honour Grandpapa’s memory means honouring everyone traumatized by this never-ending violence: both the murdered Jews from the Holocaust, and all of the Palestinians who are currently still suffering the exact same fate today.

Thank you for reading. If you like my writing and want to support me, please consider subscribing to my newsletter.

Some Writers and Articles I’ve Been Reading on Substack:

30 Usefull Concepts (Spring 2024) by Gurwinder

On Israel, student courage exposes elite cowardice by Aaron Mate

Did We Take a Wrong Turn at the Renaissance? by Mr. Raven

Free Speech Dies, Dissent Faces Suppression by George Hazim

Canada Can’t Impeach Scandal-Plagued PM Justin Trudeau, but the Liberal Party Sort of Can by Elbert King Paul

Gen Z is Doomed by Peter St Onge

Thanks for this thoughtful post, Eleanor.

I worry also about the people in Palestine, and the PTSD the survivors of this genocide will probably experience for the rest of their lives.

So sad that your grandfather was so unhappy. I have family members who have PTSD as well, and it can be extremely difficult having meaningful relationships with them.