Nazis & the Occult: What it Means for Political Beliefs to Become “Cultish”

The influence of symbology and rituals on mass psychology

Last week, as I watched Elon Musk raise a Nazi salute at Trump’s inauguration, I thought about Nazis and occult symbology. As Israel slaughters Palestinians based on fascist, extremist beliefs, Trump makes creepy comments about Gaza’s coveted location, and Nazis begin to enter every topic of political discussion, I have been thinking more and more of how the world wars never really ended. I was not yet born when the Berlin Wall came down, and so I thought that the Cold War and the Red Scare were over. I was not alive when the Nazis ruled the world, and so I thought they had been defeated. But indeed, the Nazis who escaped did go somewhere. Their ideologies continue to live on.

Often, engaging in political groups, activism and political engagement is well intentioned. It comes simply from being civic-minded—from wanting the best for your community and your people. But sometimes, unknowingly, we get absorbed into groupthink. The power of the group becomes too strong, and we develop a cult mentality.

We don’t think it could happen to us. Maybe we think we’re smarter than our ancestors; less naïve or less malleable. We like to think we’d notice. But imagine if you did live in Nazi Germany in the 1940s. Standing inside of it, with your entire society and all of your friends in family adhering to certain thought patterns and beliefs, would you actually be able to recognize it? With the normalization of cult mentality, and the social pressure to keep to it, would you actually, realistically, be able to disengage?

Cult mentality exists in our contemporary period. The word “cult” has often been employed when referring to Maga Trumpers, and for good reason. Donald Trump certainly does have near-mythical status amongst his base, and the Maga faction certainly does accept whatever he says purely on the basis that it was him that said it. But the left has similarly been accused of a cult mentality; there is too an ideological rigidity to “woke culture” which employs social exclusion if one expresses criticism or dissent to certain orthodoxies.

But the right and left always attack each other for everything. The major problem when it comes to identifying political cults is that while people can easily identify cults when they are ones to which they do not belong, they quite often fail to notice dynamics within their own groups. This is for a variety of reasons, including cognitive dissonance, ingroup bias, and the social identity theory, which basically means that once one has joined a group, they are more likely to incorporate their membership as a part of that group into their self-concept and identity.

There is nothing wrong inherently with participating in political groups. But how can one know when one is simply supporting a political group, and when one has begun to lose individual analysis and will? When are we just throwing out the word “cult” to attack someone else’s politics, and when can political beliefs or parties be fairly characterized as dangerous and cultish?

Occult Practices of the Nazis

The National Socialist (Nazi) Party under Adolf Hitler utilized occult practices to influence the psychology of their populaces. I don’t mean they participated in cult-like behaviour. I mean they were literally deliberately using occult practices to encourage cult behaviour. Whether you are a believer or a skeptic in that kind of thing, the Nazis show that there is a precedent in history for using these practices upon populaces in order to exert if not supernatural power, then at least significant psychological influence. The Nazis employed use of the occult with the intention of encouraging unity, discouraging dissent, and creating an aura of mystique and mythical status around the party. By engaging in these practices that were on the surface innocuous, populaces unknowingly legitimized Nazi rule.

For example, one common practice utilized within the occult is the use of symbology. The swastika is the most famous one, appropriated by the Nazis as a representation of Aryan identity and power. Some people don’t know the swastika was not originally a negative symbol—this is important to remember because it can help us understand that when the swastika was originally introduced to the Germans, it had no negative connotation and therefore no reason to resist it. The symbol actually derived from an ancient ideogram found in Sumeria in about 3000 BC, and it was even previously used by the Buddha, as it used to signify positive meaning. The swastika’s name derives from the Sanskirt su for “well” and asti for “being;” it was a symbol associated with the sun, power, the life force, and cyclical regeneration.

Symbology—like flags, logos, or iconic images—can be employed in politics because they are influential on people’s psyches. Symbols condense and distill complex ideas into simple visual representations, which are able to evoke strong emotions without having to use language that can be torn apart of criticized. The swastika was not the only symbol the Nazis employed—they also used occult-like runes and skull imagery, derived from esoteric traditions and Germanic mythology.

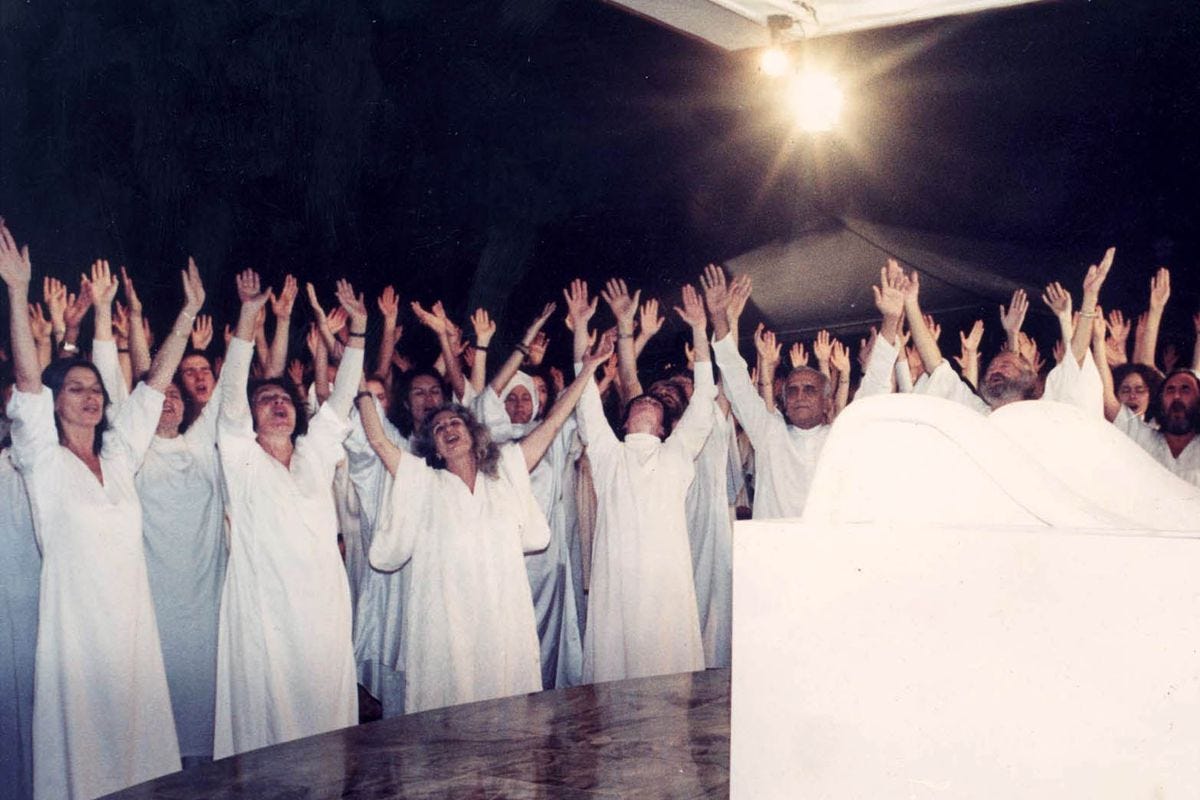

The occult also involves the use of ritual (ie, salutes, marches, ceremonies, recitations) to foster a sense of group identity and cohesion. For the Nazis, this included the infamous Nazi salute, but also things like new holidays and official calendars that encouraged populaces to engage in celebrations that were encompassing of Nazi ideas and policies. Reich Youth Day, for example, was a day to celebrate the Hitler Youth and encourage youth participation in the ideology. The Nazis also strove to decrease the influence of Christianity on their people by reframing Christmas as a celebration of Germanic traditions rather than a Christian god. This was done because it is easier to control a populace who has only one religion—loyalty to the state. A nonreligious person, while no less intelligent, is less likely to have firm competing doctrines that present alternate perspectives on morality.

Rituals are also influential on populaces as repetition is a brainwashing technique. Repeated exposure to ideas can strengthen ideas in one’s mind, and repeated statements are more likely to be perceived as true because of the illusory truth effect. The use of rituals also reinforce loyalty and create a shared purpose. Psychologically, repeated exposure to participation in rituals ingrains them into your daily life. They thus at some point become a part of your identity, which makes it more difficult to question the practice, as well as the group to which you belong.

Consider the pledge of allegiance for example. This can in fact be considered a practice with occult principles. It is more normalized to criticize this ritual now, but back in the day, it was way more challenging to do so due to the social aspect. Imagine participating in the ritual every day with the rest of your class for years, where it was incredibly normalized and accepted as a gesture of loyalty to your country, and then one day refusing. You might get some shitty looks, get criticized for not being patriotic, or become seen as someone who doesn’t care about your people. Rituals signal loyalty, and create social pressure to conform. If you do not engage, you may be out-grouped. So social pressure keeps you repeating it, even if you’re not really aware it’s happening.

When does a political group or party become “cultish?”

Groups or parties begin to become cultish when they exhibit characteristics of undue influence, uncritical loyalty, and behaviours that take on a religious dimension. This means a deep, unquestioning faith that transforms political ideology into dogmas rather than frameworks for debate and problem-solving.

As well as rituals and symbols, cults often have:

a) charismatic leadership with mythical status, who are often viewed as infallible;

b) ideologies that are inflexible and treated as ultimate truth, and cannot be questioned or critiqued;

c) dissent that is punished or silenced. Punishments do not have to be physical and can simply be a practice of shame or social exclusion;

d) a rigid sense of “Us vs Them” in-group loyalty, which dehumanizes outsiders or opposition and labels them as enemies or threats;

e) information that is controlled and tightly regulated;

f) a practice of discouraging independent thought;

g) emotional manipulation to maintain compliance and suppress doubt.

In cults, individual thought disappears. So if you’re adhering to a political group or party, and you haven’t heard any new ideas for a long, long time, that might be your first clue.

Dangers of Cult Mentality

People can be easily drawn into cults because they often feel inclusive and nice at first. They often lead with positive language, and there is often something appealing about their ideas and ideologies.

But extreme loyalty to political groups, ideologies, and ideas encourage betrayal and divide you from others. With oppressive governments, it happens beginning when people are young. The Hitler Youth and League of German Girls, for example, indoctrinated children with Nazi ideology from an early age. These organizations emphasized loyalty to the party above all else, including family. Children betrayed their own families to the Nazis. Walter Hess for example reported his father for criticizing Hitler, and his father was later arrested and executed. But Walter himself does not actually alone deserve the blame for this. His country was oppressive; dissenters were labeled as enemies of the state, and propaganda dehumanized them. In general, ordinary citizens were encouraged to ostracize people who did not conform.

Does any of this extreme loyalty to the state sound familiar?

Cult behaviour happens with both right-wing and left-wing oppressive governments. All oppressive governments are capable of it. During the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76 in China for example, Mao Zedong mobilized youth through the Red Guards, urging them to attack “counter-revolutionaries.” The concept of “Breaking the Four Olds” (old customs, culture, habits, and ideas) led to students and children denouncing their parents, teachers, and elders for perceived disloyalty to Mao. Teenager Zhang Hongbing for example reported his mother to authorities for criticizing Mao, and she was also arrested and executed.

Maybe you think, “well, those were dictatorships of the past,” as in the West, we like to believe we are free. When people talk about the negativity and divisions that have happened in our world, the only scapegoats we can think to blame are each other—our family, friends, neighbours, and community. But all the needless wars in the Middle East and the genocide in Palestine has shown that Western leaders, both right and left, are not benevolent, because they don’t care about preserving human life. America and much of the West voted against ceasefires again and again even when Hamas agreed to their demands. They supported and disseminated Zionist propaganda so their populaces would not understand the extent of the deliberate devastation. They sent money and weapons for Israel’s war crimes so people could continue receiving Zionist lobbyist money, and their forever wars made Western populaces poorer as the rich got richer.

This proves we’re not led by benevolent people. We’re just not. Look at how little Americans received for the Californian wildfires, when they clearly have enough money for Israel. In Canada, people are living in basements, in tiny boxes, and on the streets. Canadians cannot afford to treat their mental health or enter rehabilitation programs or afford medication. Our politicians had to sit down, look at Palestine and look at their domestic situations, and they still decided this money was better suited for murdering foreign children. Our Western leaders did not ask us for our consent for this. We did not get to decide.

Most Western populaces are now overwhelmingly more pro-Palestine. But our leaders do not care what we think, and you’re not supposed to get a vote. You’re instead supposed to think: well, there’s nothing I can do. But if you don’t get a vote, that is not democratic.

Given everything I have just written above about the influence of symbology on populaces, consider this contemporary example. In Vancouver, Canada, we have a connected system of libraries throughout the city called the VPL. That article in the Vancouver Sun is about how the VPL has banned pro-Palestinian staffers from wearing watermelon pins. The watermelon, a symbol for resistance against Israeli oppression, apartheid, and genocide, is banned because it “hurts some people’s feelings” per the spokesperson, reframing it as “bullying” Zionists. So the VPL is trying to seem anti-bullying while being pro-genocide.

I draw attention to this example because the article discusses how VPL is okay with pro-Ukrainian pins, rainbow flag pins, or poppies as symbols of political expression. So why is the VPL trying to control symbology? Probably the same reason why a government would threaten leaders of universities of withholding money if they do not focus on antisemitism messaging alone. The VPL isn’t choosing their own symbology; as a public library, it receives its funding from municipal and federal governments, so their symbols had to first be approved by the state. But if it’s a democracy, why should our choice of symbols be so threatening to institutional power that they might withhold funding if the right symbols are not chosen?

So it is quite valid to be concerned about Elon Musk’s Nazi salute. But we also must be mindful of that symbols and rituals look different in the new age, and take on different dimensions.

How do I know if I am falling into groupthink?

You just need ongoing self-awareness and self-assessment. Since 2022 and during the time I begun this Substack, I began reassessing why I believe anything I believe. Where did those ideas come from? Why do I believe that? Do I believe that because it’s my actual opinion, or because everyone around me believes it? Was I wrong about anything I have supported in the past? Why? Can I admit when I am wrong? Did I once believe ideologies because they were based on accurate information, or did I believe them because I read a thinkpiece by a “reputable” source that turned out to not actually be reputable? Do I rely on arguments of authority to convince me as to what is true?

To avoid cult-like groupthink, one must regularly question your own beliefs and assumptions. Seek out information from actually diverse sources, meaning sources that are not just right vs. left and are ones that do not agree with one another, or even criticize one another. We must also always avoid blind loyalty to any party, leader, or group, even if you believe the opposing parties or leaders are worse. Evaluate whether these groups treat ideas as inflexible, and be wary of group pressure.

We must also keep connections with people outside our groups. Dissent should be tolerated, open dialogue encouraged. No one should be attacking your character but your ideas, and we must be countering information with other information.

We are not party representatives, after all. We are individuals, so we represent ourselves alone.

Articles and writers I’ve been reading:

Gaza double-standards show everything we were told about Western democracy is a lie by Ricky Hale and Council Estate Media

Rubio Touts ‘Partnership’ with Fellow Israel Fanatic Brian Mast by Decensored News

India's invisible hand in Israel's AI war in Gaza by Azad Essa

BRICS expands to 54.6% of world population by adding Nigeria, Africa's most populous country by Ben Norton

I Do Nothing at Work and No One Seems To Notice or Care by Antonio Melonio

The Israeli Military Is One of Microsoft's Top AI Customers, Leaked Documents Reveal by Ryan Grim and Waqas Ahmed

Israel Invades Jenin Days After Signing Gaza “Ceasefire” by Sharif Abdel Kouddous and Mariam Barghouti

Great essay, plenty food for thought, thanks for that