How Often Do Chaos Agents Provoke Revolutions?

On Narodnaya Volya and the Assassination of Tsar Alexander II

I fear we are living in what will eventually be a Theatrum Mundi painting. Those are “chaos compositions,” which depict apocalyptic scenes like wars, plagues, and falls of empires. They often depict numerous figures in disarray, but though those individuals fight, or flee, or weep, or die, the individuals themselves don’t really matter. They are not the subject of the painting; the subject is the event.

Now though, I think of those individuals, the nameless that endured big moments in history only to disappear without ever having recorded their own perspectives. Did they know what was happening while it was happening, or were they completely unprepared for what took place? Did they have any agency at all to affect the outcome of the composition? Or were they always at the behest of larger, more powerful players, who controlled and affected their futures in ways that they would never be capable of doing themselves?

Sometimes when you read through history you’ll occasionally feel a sense of kinship to historical figures. I think this is important; to remember our history and remember the importance of loss of life. Lately I feel a connection to ghosts that have no names: the Russian peasantry of the turn of the 20th century. They lived during the time of Narodniks, and the Bolshevik Revolution that followed. Many of them suffered immensely during this era, but often had minimal control over their destinies. Meanwhile, more powerful players directed events that significantly impacted and worsened their lives, and what happened to them because of a terrorist group called Narodnaya Volya in the 1880s reminds me very much of what we are going through now.

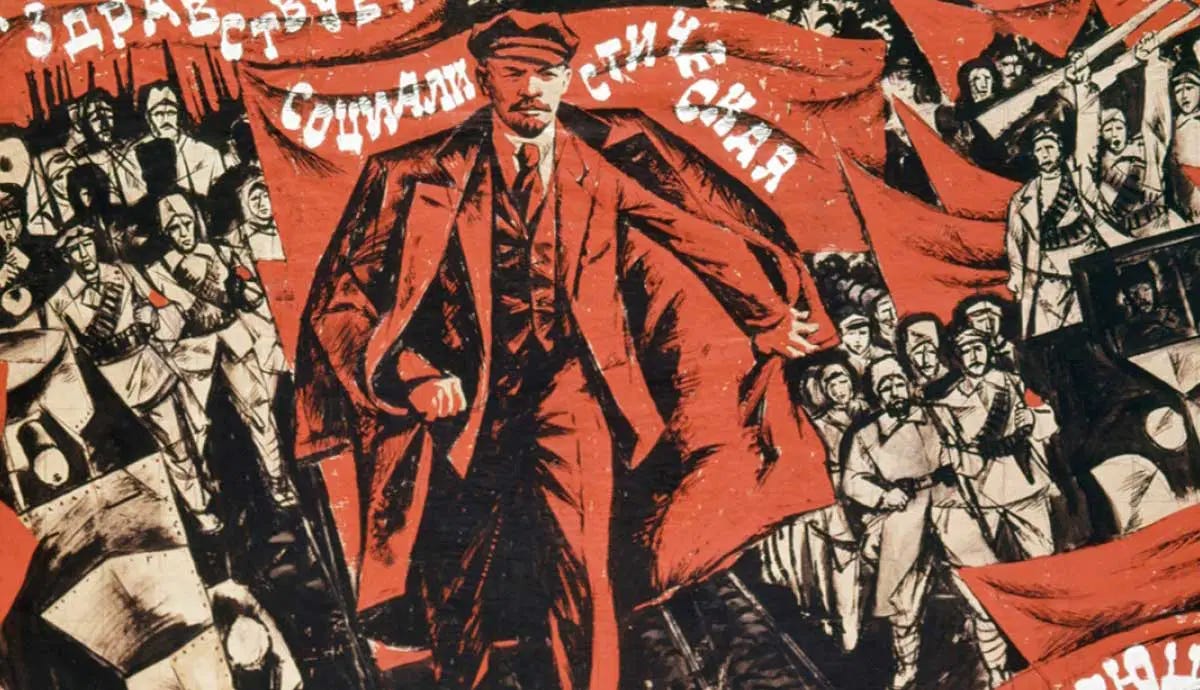

At the turn of the twentieth century, there were groups of intelligentsia living in the Russian Empire who were known as the Narodniks. Narodniks were revolutionary socialists, and included notable figures like Aleksandr Ulyanov, who was the brother of Vladimir Lenin. Narodniks believed in social revolution, and their goals were to destroy the Russian monarchy and distribute the land equally among the peasantry. They believed the peasantry were the key to achieving their goals, so they established semi-secret societies like the Circle of Tchaikovsky and Land and Liberty, where they worked on propaganda campaigns to manipulate the peasantry into actions the Narodniks believed was necessary to inspire revolution.

The Narodniks purported to care about the peasantry and the working class, and some historical records overly romanticize them for their revolutionary spirit. However, like the Fabians and their eugenics policies, many Narodniks employed top-down methods and held elitist perspectives regarding the Russian peasantry. Many Narodniks, including those in Narodnaya Volya, were actually Russian nobility themselves, and most did not believe the peasantry were capable of understanding why revolution was important or believed they would be capable of achieving it on their own. Their philosophies thus required the propaganda operations to persuade or provoke the peasantry into revolution, regardless of what the peasantry’s input. And in the case of Narodnaya Volya—which split from Land and Liberty in 1879—they also wanted to inspire revolution through acts of terrorism. They called it “propaganda by deed,” or a direct action that was meant to serve as an example for others to follow. A catalyst for social revolution.

Narodnaya Volya typically claimed to care about the Russian peasantry, however, while they claimed to work for the people, rarely did they actually work with them. Though Narodniks sometimes were lionized in the twentieth century for their anti-tsarist beliefs, they read a little like champagne socialists, their class status and privilege perhaps inspiring a sense of guilt they wanted to assuage through social activism. While they declared a dedication to the peasantry, they were paternalistic, and there is little evidence that they actually listened to the peasantry’s actual perspectives on anything. It is reminiscent of what we endure today.

There is limited evidence that the Russian peasantry actually wanted revolution. It was not that they believed they were thriving beneath Tsar Alexander II—they did have grievances, particularly was it related to land redistribution. However, most peasants did not actually have a negative view of the Tsar himself. They saw him as a sacred, mostly benevolent paternal figure, and revered him while blaming issues mostly on intermediaries:

“[The Russian peasant] regarded the tsar as God’s vicar on earth… He believed the tsar knew him personally and that if he were to knock on the door of the Winter Palace he would be warmly received and his complaints not only heard but understood in the minutest detail.” – Historian Richard Pipes

The Narodniks however believed that because of their superior education, the peasantry just did not know what was good for them, thus educated elites had a moral obligation to “go to the people” and awaken their revolutionary consciousness. There was a movement in the 1870s literally called “Going to the People,” which consisted of radicals like Andrei Zhelyabov and Sofia Perovskaya visiting Russian villages to try and radicalize them. During the “Mad Summer of 1874,” elite intellectuals even dressed up as peasants to propagandize the peasantry. “Going to the People” however mostly failed, because most of the peasants found the Narodniks more suspicious than the Tsar. They even reported the revolutionaries to the police due to their mistrust. “Going to the People” thus appeared more like manipulation than authentic connection to the peasantry or their wishes.

Unsuccessful in their attempts to provoke a revolution, Narodnaya Volya turned to terrorism. They assassinated Kharkov Governor Dmitry Kropotkin in February 1879, and in November 1879 made three attempts to blow up a train returning from Crimea in an attempt to kill Tsar Alexander II. In February 1880, Stepan Khalturin placed explosives in the Winter Palace, and the group made two more failed attempts in 1880 before the assassination was ultimately successful in 1881.

The Russian peasantry as I’ve said was not flourishing with Tsar Alexander II, however, he had been passing more liberal policies, and after his death, Russia entered an era that was even more tense and difficult. Many of Alexander II’s more liberal reforms were repealed, and by the end of WWI, the monarchy was in such a weakened position that it made them susceptible to being overthrown by the Bolsheviks.

What is important to note is that while things were hard for the peasantry with the Tsars, with the Bolsheviks, life became even worse. Initially, land was redistributed amongst the peasants, but Bolshevik policies like war communism and forced collectivization resulted in mass suffering amongst the common folk. Between 1918 and 1921, the Bolsheviks requisitioned grain forcefully to feed urban areas and the Red Army, and if peasants resisted, they were labelled kulaks and targeted. Though the peasantry had had grievances with Tsar Alexander II, they never rose against him, however 1920-21 saw the Tambov Rebellion, which ended with 15,000 dead and 50,000 civilians interned in camps.

My point of this is that while Narodnaya Volya claimed to care about the peasantry, the assassination of the Tsar was not actually to their benefit, and nor did they even ask for it. The group engaged in manipulative propaganda practices, and ultimately created a situation that was ultimately even worse for the Russian peasantry.

The Romanovs were likely destined to be overthrown, and it is not that they were without criticism themselves. But what intrigues me about this story is that, like the practice of propagandizing populaces into supporting wars, the practice of manipulating “peasants” into revolutions and civil wars also continues to this day. Except instead of revolutionary groups practicing this manipulation, it is our governments and their intelligence branches.

We would be wise to remind ourselves of this as we were propagandized into supporting a terrorist state at the expense of millions of lives, and now they are working on propaganda to drag us into a war in Iran.

We would be wise to remind ourselves of this as we were propagandized into funding a proxy war in Ukraine.

We would be wise to remind ourselves of this as we were propagandized into euthanizing ourselves.

We are but Russian peasants, at the whim of the powerful.

Do the Masses ever really get to decide the direction of our lives?

The story of Narodnaya Volya thus invites an interesting question—have elites and manipulative players always tried to provoke violence and revolution for the purpose of regime change? How many revolutions in history happened because a populace actually wanted it, and how many happened because they were provoked by manipulative players? Recall Euromaidan in Ukraine, the Sunflower Revolution in Taiwan, and the Umbrella Revolution in Hong Kong are only a few examples of how this can happen.

How do we know when a a revolution is the true voice of the people, and how do we know when events are being manipulated by Chaos Agents?

Thank you for reading.

***An important note: If you care about stopping the genocide in Palestine, do not support waging war in Iran. Israel is a terrorist state and Iran has the right to defend itself. Israel’s reign of terror must end and they must be cut off from support from the West. If you live in a Western nation, resist war with Iran at all costs.